In the 2022 midterm elections, Latino voters comprised 14% of the electorate, representing one of the fastest-growing blocks of voters in the United States. But not every Latino individual who lives here is eligible to vote — many are here under a temporary status or as legal permanent residents while others are unauthorized.

Kennia Coronado, a doctoral student in the Department of Political Science, studies political participation and Latino political behavior. As she was researching Wisconsin and other key swing states, she noticed something fascinating: Even in cases when Latino individuals were ineligible to vote — because of their citizenship status, their voter registration status or a host of other reasons — some were still participating in the political process.

Intrigued, Coronado wanted to know how it was happening.

“What I'm really looking at is, aside from the major political parties, how do Latinos mobilize themselves?” asks Coronado, who grew up in Southeastern Wisconsin. “There is no real infrastructure on behalf of the parties to mobilize what may be considered immigrant-based communities.”

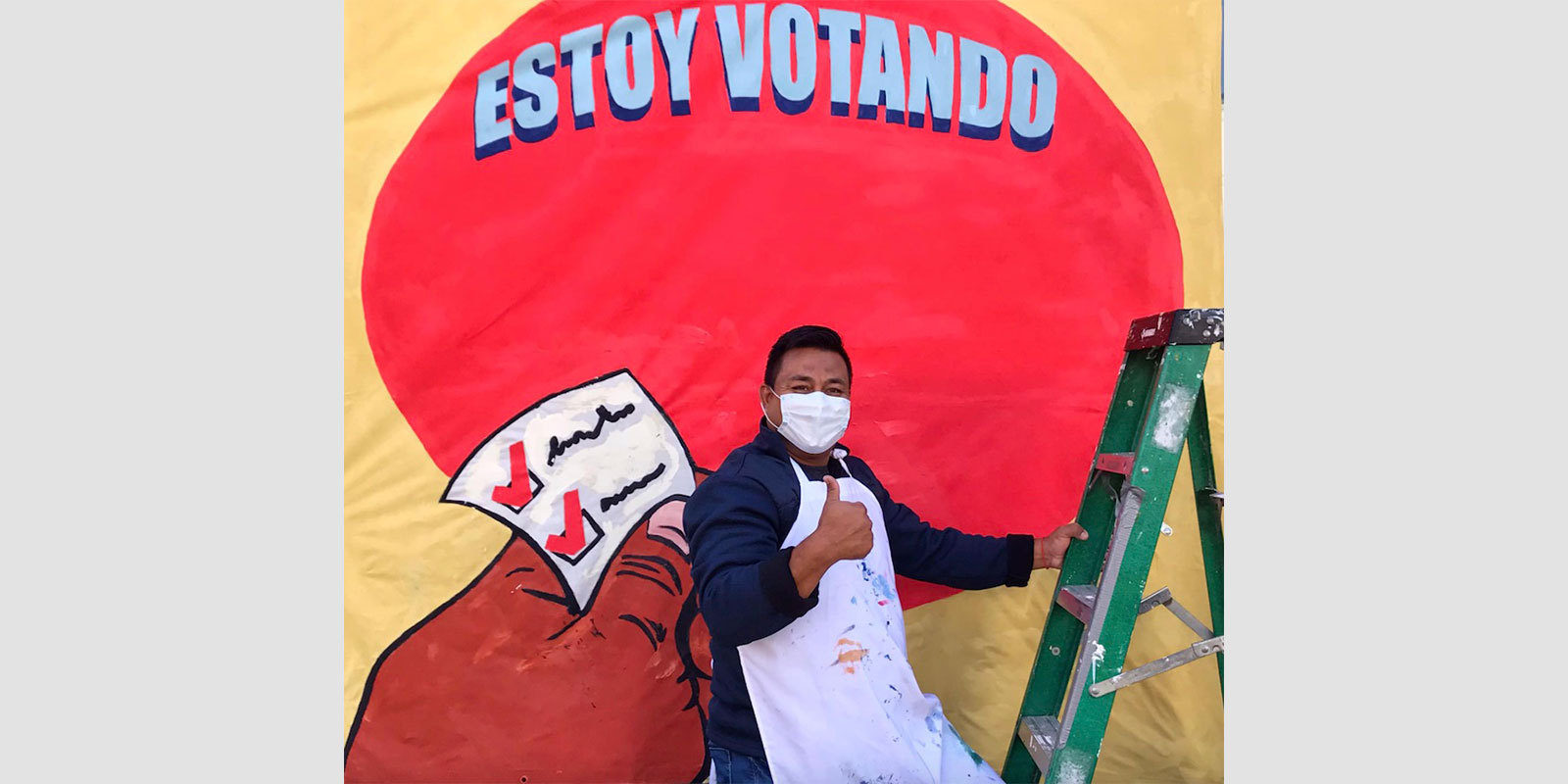

Coronado discovered a network of what she calls “co-ethnic intermediaries,” which are local organizations working to educate and turn out Latino voters. That network includes immigrant advocacy organizations and activists that came out of the DREAMer movement of the early 2000s, some of whom had served in roles on national presidential campaigns. She also found Spanish language radio stations working in conjunction with these groups to mobilize voting-eligible Latinos to the polls.

“Some of these organizations and individuals are advocating for immigrant rights, but they broadly mobilize and incorporate Latinos into their electoral work, into the work that they do around diverse policy areas,” says Coronado. “And that encompasses a whole range of Latinos, people who are voting eligible and non-voting eligible.”

Coronado notes that several of these organizations have both a nonprofit and an advocacy wing. The former is allowed to instruct and assist members in the political process and registering to vote, but only in a non-partisan way, and is prohibited from endorsing or campaigning on behalf of a candidate. In the latter, the membership can decide if they want to endorse a candidate and mobilize through their organization in support.

While the primary goal of these organizations is often mobilizing as many voters to the polls as possible, Coronado found there’s also a longer-term objective: building a political infrastructure in the communities that can be leveraged in future elections.

“Let's say that you have a legal permanent resident who is helping register voting-eligible people in their community,” says Coronado. “Maybe in the short term, they can't vote, but a few years from now, they can naturalize as a U.S. citizen, and they now understand how they can go about voting.”

Coronado looked at Latino political activity in several states across the country, noticing that it’s different in states like Texas and North Carolina, places in which Latinos experience immigration surveillance policies very differently.

For Latino individuals who are in the United States under an unauthorized status, participation in the political process poses a risk — and yet some of them still choose to do so. None of the ineligible voters that Coronado interviewed cast a vote, because they knew it was illegal to do so. Instead, they discussed finding other methods of participation, from volunteering on campaigns to calling people in their community. That participation, she found, can prove valuable.

“When these individuals are working on campaigns, they understand how to engage the full spectrum of voters from the ground up,” says Coronado. “Which is often something that political strategists and campaigns overlook, because they don't have the experiences that people in these communities might have.”

Coronado’s research also confirmed what she and other political experts already knew —Latino voters are not a monolithic block. Neither Democrats nor Republicans have an unshakeable claim on their support, and both parties have struggled to connect to Latino voters on issues like immigration and workers’ rights. Still, in an election environment in which 20,000 votes can swing a key local or national election, there’s no question that understanding how they’re participating in the political process is important.

Coronado is currently spending her semester doing pre-doctorate work at the University of Pennsylvania before returning to Wisconsin in 2024 — the year of the next U.S. presidential election. She’s looking forward to tracking how the Latino community responds.

“The story is really about the ways Latinos eventually become voters,” she says. “It’s a process that changes with their legal status along the way. We’re trying to figure out how Latinos become incorporated as they eventually naturalize.”