Years ago, while pursuing a history of science PhD at UW-Madison, Anna Zeide embarked on an academic journey that would crack open a fascinating history, one that had sat preserved on a shelf for decades.

Zeide came to Wisconsin with an interest in food history. So when professor Bill Cronon commented that forms of food preservation are the foundations on which societies are built, she knew she was on to something. Her research led her to the history of canning — specifically the incredible societal shifts that took place once the technique became commercialized.

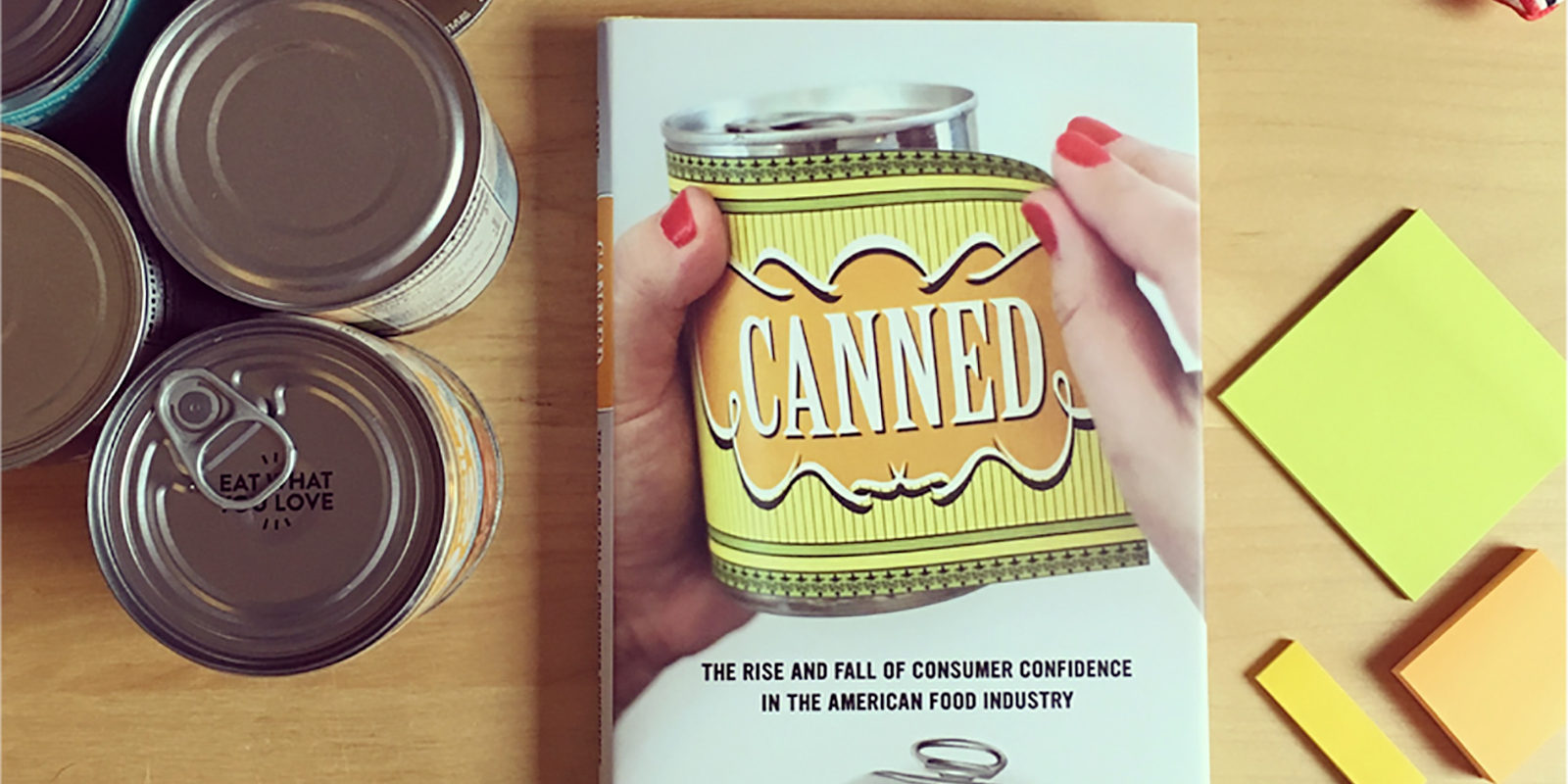

Zeide’s book on the topic, Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry, published in April 2018, is the first in-depth study on the history of canned foods. It won the 2019 award for best Reference, History and Scholarship book from the James Beard Foundation. Zeide also presented on the book at the Wisconsin Book Festival in Madison this fall.

As Zeide began digging into the topic of food preservation, she made an interesting discovery: When canning moved from a local practice of preserving fruits, vegetables and meats to an industrialized, for-profit process of preparing foods for distribution, it set the stage for the food industry as we know it today. As canning transitioned into the factory and laboratory, it paved the way for an age in which packaged foods are often cheaper and more readily available than fresh items.

“The canning industry was the earliest incarnation of the modern food industry,” says Zeide.

And it was one that grew rapidly. Zeide learned that the first commercial canneries in the United States opened in the 1850s, and that by the turn of the century, there were more than 2,500 operations across the country. In 1914, canneries produced more than 73 million cases of food; by 1961, the number reached 722 million.

In her book, Zeide narrates how the industrialized food industry took shape, and how Americans were taught to trust what was hidden inside those shiny metal cans, thanks to the powers of marketing, politics and science.

“When we open up the can, we see it becomes a lens through which we can understand social organization, science and technology, corporations, politics, marketing, labor and the environment — and the way that all of these come together through the food industry,” Zeide explains in the book’s introduction.

While Cannedis a work of history, Zeide wrote it for a readership beyond academia. Her experiences at UW-Madison, specifically the Mellon Public Humanities Fellowship offered by the Center for the Humanities — through which she developed sustainability and health initiatives for the Madison Children’s Museum — reinforced, for her, the importance of bringing humanities expertise and scholarship into the world.

And of course, everyone has a relationship with food. Learning about its history “forces us to look deeper behind the scenes at what’s taken for granted,” Zeide says. “It changes the way you think about how everything fits.”

You start asking questions about access and for whom food systems are built, Zeide says. And about assumptions, such as the connections between canned food and food drives, food pantries and poverty, or the notion that fresh food is a luxury for the elite.

People often ask Zeide, who completed her PhD in 2014 and now teaches history and food studies at Oklahoma State University,whether canned food is “bad,” and what can be done to reverse the trend toward more factory-produced food. Should they choose organic foods? Grow their own vegetables?

“The answer, of course, is complicated,” she says. “Those questions are very tied to food justice and social justice — to food deserts, access to healthy soil and more.”

Zeide sees her role as raising awareness about the complexities and history of food systems. And she has two new books in the works. One offers an overview of U.S. history through 15 foods, and the other is on the history of food waste, exploring landfills, compost, regulation, the climate crisis and alternative methods to waste.

As she delves into research on the latter project, she’s finding herself in familiar territory.

“Again, it’s one of those topics that leads to everything,” she says. “Questions about food, consumption and disposal permeate our daily lives.”