As the holidays approach, many gift-givers will pore over the American Girl catalog and website. The Middleton-based company, now owned by Mattel, has been selling dolls, accessories and books focused on a wide range of historical periods and cultural perspectives since 1986.

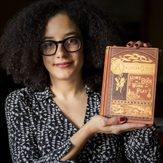

And in a few weeks, comparative literature assistant professor Brigitte Fielder will lead a class examining the company and its approach to American girlhood.

American Girls & American Girlhood explores the stories of Kirstin, Addy, Kaya, Kit and others alongside literary texts written for both children and adults. It’s been a popular course each spring semester, attracting many students who grew up with the iconic series of dolls and books.

Works such as Little Women by Louisa May Alcott; The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison; Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, an autobiography by Harriet Jacobs; American Indian Stories by Zitkala-Ša, a Dakota Sioux writer; and children’s literature from 19th century offer rich contrasts.

I frame the class in part around the notion of American girlhood, what it means to be American, what it means to be a girl, what it means to be an American girl.

For instance, the story of Addy, the fifth American Girl doll and the company’s first African American character, tells of her and her mother’s escape from slavery and the racism they experience in Philadelphia in the 1860s. But it doesn’t touch on the more severe threats that works of the period don’t shy away from revealing, Fielder says.

“Abolitionist children’s literature is often very dark,” Fielder says. “Students are often surprised about how sad it is. But the impetus is often not to give it a happy ending.”

Fielder — who won the inaugural social justice award in July from the Lydia Maria Child Society, named for the 19th century writer — also uses the books to guide students in probing definitions of both “American” and girl.”

“I frame the class in part around the notion of American girlhood, what it means to be American, what it means to be a girl, what it means to be an American girl,” she says. “American Girl as a company construes American girlhood broadly, to contain children who were not considered American.”

Interestingly, several American Girl characters would not have been considered American in their lifetimes, Fielder says. Formerly enslaved people like Addy didn’t enjoy full rights, while Felicity’s story is set at the start of the American Revolution and Josephina lived in what was Mexico in the 1820s. And Kaya is part of the Nez Perce tribe, living in the Northwest in 1764 before the arrival of Europeans; Fielder contrasts her story with experiences of Native American children forced into boarding schools told in American Indian Stories.

To extend such analysis into the present day, Fielder assigns students to write blog posts about something they’ve encountered — perhaps an advertisement, music video, film or news story — and relate it to concepts, terms and readings they’ve discussed in class.

“In general, I hope they learn some critical thinking skills for thinking about gender, race and childhood as they encounter it in the world.”