Back when timber wolves still roamed Madison’s forested isthmus, a liberal arts tradition was taking shape at the University of Wisconsin.

The first students (there were 17 enrolled in the inaugural freshman class in 1849) focused primarily on ancient Latin and Greek, just as students did at Harvard and Yale.

But upperclassmen could also choose courses in chemistry, international law, and political economy. Some Easterners believed courses like these were too “practical” and “modern” for a college curriculum.

But here at Wisconsin, a different plan was unfolding.

“We are about laying the foundations of an Institution of learning, which we believe is destined to exert a great and salutary influence on the moral, intellectual, and social character of the people of this State, for all time to come,” declared Eleazer Root, President of the first Board of Regents, as he greeted the first chancellor, John Lathrop, in 1849.

“All the people of the state” didn’t just mean the elite. It meant the sons of farmers and immigrants, too. From the beginning, university leaders were drawn to the idea that the liberal arts would enrich everything – that specialists in trades or professions would benefit from studying philosophy, languages, literature, higher mathematics. This general leaning eventually hardened into a bedrock value that would shape the university over the next 150 years.

Laying a firm foundation

Today the College of Letters & Science is the largest unit on campus, graduating more than 3,000 students each year and teaching more than 60 percent of all the credits offered at UW-Madison.

From just 34 professors, L&S now contains multitudes: neurobiologists, philosophers, economists, musicians, and chemists. Filmmakers, writers, language specialists, and astrophysicists. Geologists, anthropologists, historians, psychologists—all pushing the boundaries of research and helping to change the world.

And while today’s classics students still read Homer, they might also travel to real-life Troy to help perform biochemical research on artifacts that shed further light on the people and customs immortalized by Homer in the Iliad.

French, German, and Norwegian programs are still strong, but today students can also delve into Arabic, Swahili, Pashto, Portuguese, Russian, Mandarin and 63 other languages.

Astronomy students may still marvel at the night sky at Washburn Observatory (which helped put Wisconsin on the map as a scientific research powerhouse in 1878), but they will learn even more about the universe from Ice Cube, the world’s largest neutrino observatory buried deep in Antarctica.

Land Grant Supports Liberal Arts

The 1862 Morrill Land Grant Act played a defining role in the Wisconsin liberal arts tradition. Money from the federal government was on the table. Would Wisconsin use it to build a separate agricultural and technical college, as Iowa, Ohio, Michigan and other Midwestern states chose to do? Or would it combine its strengths, creating one massive university with a free exchange of knowledge between the applied sciences and the arts and letters curriculum?

A farmer from Columbia County introduced the bill that helped Wisconsin legislators make history, and laid the groundwork for the highly successful model of learning, teaching and research we know today. Instead of two universities, one great one was established in 1866 under the bill.

“Wisconsin’s acceptance of the Federal land grant ... strengthened the University’s position as a center for the liberal arts,” wrote historian John Frank Cook in “A History of Liberal Education at UW-Madison.”.

As the university grew, so did L&S. Size brought strength.

“A lot of liberal arts colleges attract students and faculty by discussing their close community and claiming that ‘small is beautiful,’ “ said Chancellor Rebecca Blank, in her State of the University address in Fall 2014. “Well, I want to announce that I’m firmly committed to the idea that, when it comes to education and research, ‘bigger is better.’”

We are about laying the foundations of an Institution of learning, which we believe is destined to exert a great and salutary influence on the moral, intellectual, and social character of the people of this State, for all time to come.

Pioneers of Scholarship

Because the state made that critical choice in the land-grant era –to build on UW’s original liberal arts curriculum, rather than establish a separate university for agriculture—highly-skilled faculty became interested in working here. Professors trained in eastern schools came west to Wisconsin, and found room to explore new ideas. Many of them introduced programs of study that broke boundaries and redefined the term “liberal education.”

Physicist John E. Davis, astronomer James C. Watson, and geologist Roland D. Irving all helped the newly-formed College of Letters & Science become a center of scientific investigation “that could not be overlooked,” by the end of the 19th century.

L&S attracted curious, innovative thinkers like Frederick Jackson Turner, who wrote and taught about the significance of the frontier in American history, and Richard T. Ely, an outstanding young economist whose hiring opened a new chapter in the study of the social sciences.

In fact, it was Ely’s teaching of “controversial subjects” such as strikes, boycotts and socialism that led to the UW Board of Regents issuing the famous “sifting and winnowing” statement in 1894, that has come to define academic freedom at UW-Madison.

And it was in L&S where the “Wisconsin Idea” took root, when history scholar Charles McCarthy proposed that University of Wisconsin expertise could and should be shared to benefit the lives of state citizens.

Great People

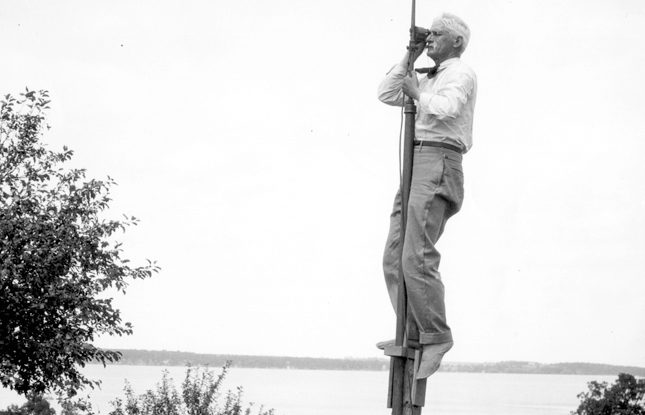

It was people who elevated this College and made it great. People like the first dean of L&S, Edward A. Birge, who for 27 years, guided the College through transformation and change but always championed the liberal arts’ role in preparing students for life.

People like English professor Helen C. White, the first female to earn the rank of full professor in L&S in 1936, who eloquently defended literature’s place in society.

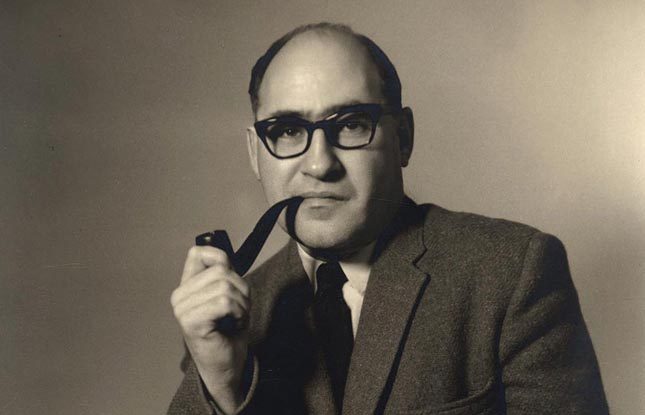

People like historian George L. Mosse, who escaped Nazi persecution and came to UW to teach European intellectual history and Jewish history. His colleagues called him “fearless in exploring difficult subjects.”

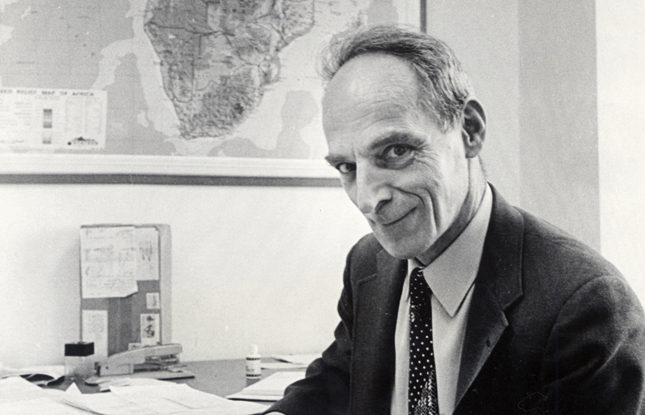

People like anthropologist and historian Jan Vansina, who reached thousands of years into the past to reclaim the “unknowable” history of Africa through oral storytelling. Vansina’s legacy extends beyond academia: he worked with journalist Alex Haley to trace his African origins, an endeavor that led to Haley’s blockbuster novel and mini-series, “Roots.”

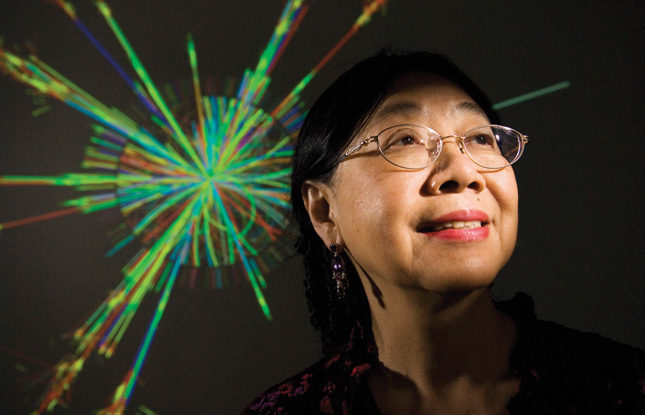

There are astounding discoveries happening in L&S today. From Sau Lan Wu’s physics team that discovered evidence of the Higgs Boson, to Francis Halzen’s neutrino detector, Ice Cube – from the Institute for Research on Poverty to the Institute for Research in the Humanities, faculty and students in the College of Letters & Science push beyond the boundaries of what we know. They share this excitement with their students in the classroom, in the lab, in the field, and throughout our communities.

The Past Informs the Present

Making connections between past and present reminds us how strong leadership, a bold course, and a commitment to bedrock values have guided L&S through more than a century of growth and change.

Dean Birge’s early conviction that “a public university should not only transmit, but increase, man’s fund of knowledge” has evolved into a direct mandate for groundbreaking research in all fields.

The first Regents’ insistence on a more practical intellectual tradition can be seen today in the new Letters & Science Career Initiative, launched by Dean Karl Scholz to provide liberal arts students with a blueprint for planning and launching their working lives.

President Thomas Chamberlin’s bold resolve, in the late 1800s, to seek nationwide for the very best professors to teach the brightest students—and keep them here—continues today, as leaders seek support to hire and retain key faculty.

And those first 17 students who, in 1849, huddled near the fire to study the ancient classics? They’re not so different than the thousands of new L&S undergraduate and graduate students arriving each fall. Bright, determined, and eager to explore new frontiers of knowledge, Wisconsin Letters & Science students are a special breed. They are leaders committed to making the world a better place. And beyond all else, we are committed to their success.